‘When did Milton Friedman die and become king?” asked presidential candidate Joe Biden in 2019. Verbal incapacity aside—presumably he meant to ask who died and made Friedman king—Mr. Biden’s use of the free-market economist’s name to signify the reigning consensus in economics was absurd as a representation of 21st-century political reality but also suggestive of Friedman’s importance.

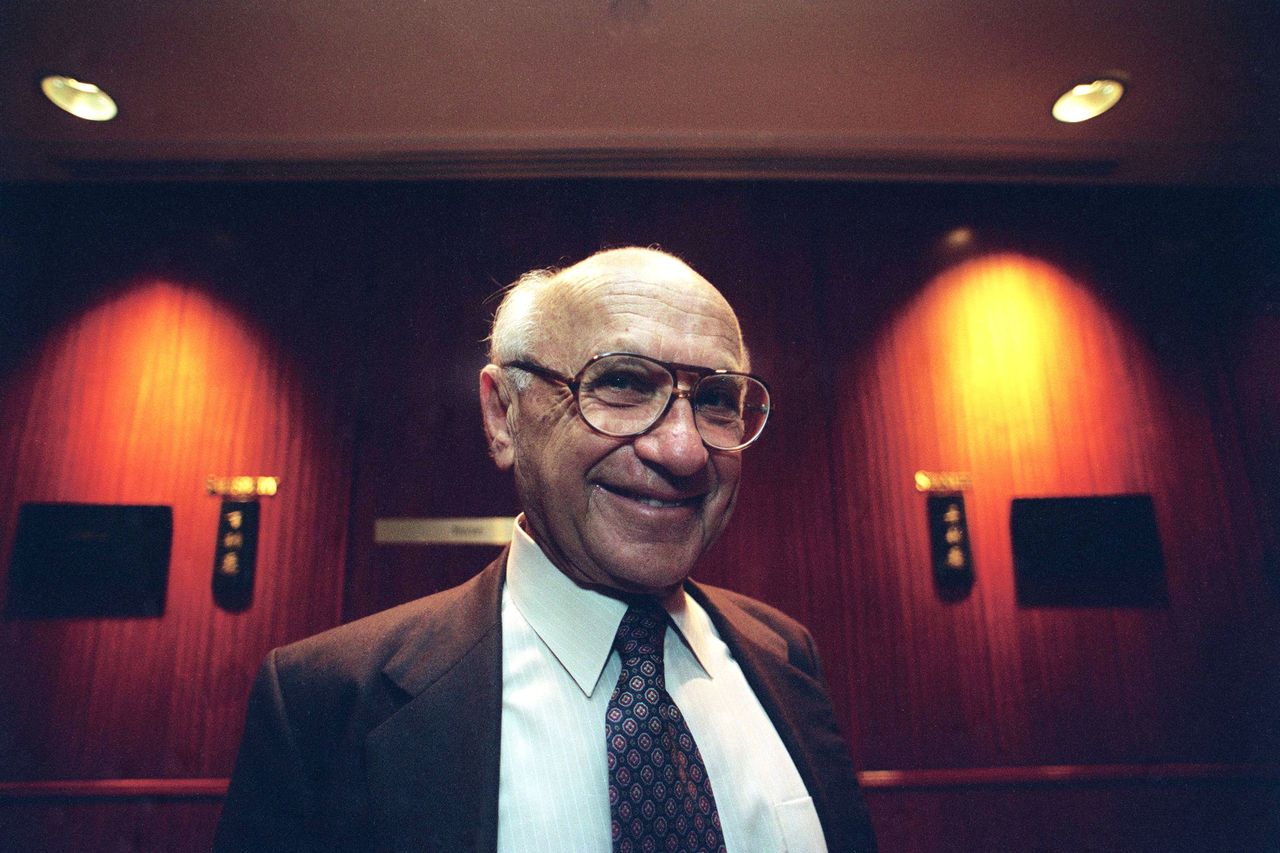

Milton Friedman (1912-2006) was at once an accomplished academic economist, an adviser to U.S. presidents and cabinet officials, and a widely read columnist. He won the Nobel Prize in 1976. The 1980 PBS series “Free to Choose,” in which Friedman and his wife, Rose, explained the virtues of markets and the follies of state planning, enabled ordinary Americans to grasp the essence of Reaganism.

“Milton Friedman: The Last Conservative,” by Jennifer Burns, a historian at Stanford, is a sympathetic intellectual biography. Ms. Burns had full access to Friedman’s papers stored at Stanford’s Hoover Institution; she has interviewed many of Friedman’s friends, colleagues and competitors; and she is plainly an authority on the at times highly abstruse subjects of economic theory and monetary policy. The book is a tremendous scholarly accomplishment.

I would not call it riveting. Five hundred pages is a lot to read on the life and thought of an economist, even one who reveled in controversy and upended paradigms. The book’s first half, in particular, is replete with discussions of rarefied disputes over economic theories and detailed accounts of status-jockeying among academics.

Readers who find these early chapters a slog may wish to skim till they get to chapter 9, “Political Economist,” in which Friedman the academic—he taught for 30 years at the University of Chicago—becomes Friedman the intellectual and polemicist. In 1963, he and co-author Anna Schwartz published “A Monetary History of the United States.” The booms and busts caused by price instability, Friedman and Schwartz argued, were the outcome of either an oversupply or undersupply of money. Not greedy robber barons or insufficient regulation but faulty monetary plumbing. The Great Depression, they argued famously, was not the result of a fear-driven drop in demand and a deficiency of government action, as Keynesian theory had led everybody to believe, but the inevitable consequence of New York Fed governor George L. Harrison’s failure to respond to the liquidity crisis of 1929 by printing more money.

In Friedman’s “monetarism,” as the doctrine was not yet called, you can see the premises of conservatism. Economic growth, in this outlook, doesn’t depend on credentialed planners knowing when to stimulate or suppress demand but on the ingenuity and industry of ordinary people. Friedman was, for many of his critics, a sort of anti-economist.

Ms. Burns’s praise for Friedman is often delicately stated and hedged. “Simply put,” she writes in the book’s concluding chapter with more ambivalence than simplicity, “Friedman is too fundamental a thinker to set aside.” On the burning economic question of the 1970s, however—inflation—Ms. Burns concludes that Friedman was basically right and his opponents and critics, particularly Fed Chairman Arthur Burns, were wrong. In 1970, soon after his appointment to the Fed, Burns delivered a speech urging the Nixon administration to fight inflation by ordering wage and price controls.

Friedman—who thought, wrongly, that Burns had accepted the arguments of “A Monetary History”—was shocked. Ms. Burns (no relation), citing unpublished letters, relates the episode: “Far more than a policy disagreement, for Friedman the speech was a profound rupture in his emotional universe. Later that evening, after hours of tossing and turning, Friedman arose from his bed and poured out his anguish. The ‘incomes policy speech’ had left him sleepless, ‘saddened, dismayed, + depressed,’ he wrote to Burns in a passionate letter.” Friedman added: “Though I know this is not fair or right or generous—the word that keeps coming to mind is ‘betrayed.’ ” His letter did not have its intended effect. The two friends fell out, Burns persuaded Nixon to order wage and price controls, and inflation came roaring back when the controls expired.

Friedman remained a fierce critic of Nixon’s economic policies. The president had George Shultz, director of the Office of Management and Budget, bring Friedman to the White House in an attempt to soften his hostility. “Don’t blame George,” the president advised his critic. Friedman’s reply: “I don’t blame George, Mr. President. I blame you.”

On one point I find Ms. Burns’s interpretation unfair. It’s a tangled subject, but to simplify: Friedman generally felt that the free market would address racial inequities more effectively than governmental attempts to dictate equality. He therefore resisted the idea, codified in Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, that government had both the ability and the moral authority to tell employers whom they could hire or businesses whom they could serve. That is not a popular view today, but its holders might reasonably claim that the private sector—sports, business—has done more than governmental compulsion to integrate the races, and less to sow discord. Yet Ms. Burns calls Friedman’s articulation of this viewpoint, expressed in his 1962 collection “Capitalism and Freedom,” an “apologia for racism.” The charge is preposterous—unless you can’t fathom a legitimate response to morally deplorable private behavior that doesn’t involve governmental coercion.

Was Friedman the “last” conservative, as the book’s subtitle has it? Ms. Burns defends that designation by noting that “the synthesis that Friedman represented—based in free market economics, individual liberty, and global cooperation—has cracked apart.” I’m not so sure. Friedman, as Ms. Burns’s book reminds us, constantly wrangled with figures on his own side, and today’s American right, for all its fractiousness, has produced no coherent alternative to that “synthesis.” Friedman isn’t king, but neither is he dead.

Mr. Swaim is an editorial page writer for the Journal.

News Related-

Russian court extends detention of Wall Street Journal reporter Evan Gershkovich, arrested on espionage charges

-

Israel's economy recovered from previous wars with Hamas, but this one might go longer, hit harder

-

Stock market today: Asian shares mixed ahead of US consumer confidence and price data

-

EXCLUSIVE: ‘Sister Wives' star Christine Brown says her kids' happy marriages inspired her leave Kody Brown

-

NBA fans roast Clippers for losing to Nuggets without Jokic, Murray, Gordon

-

Panthers-Senators brawl ends in 10-minute penalty for all players on ice

-

CNBC Daily Open: Is record Black Friday sales spike a false dawn?

-

Freed Israeli hostage describes deteriorating conditions while being held by Hamas

-

High stakes and glitz mark the vote in Paris for the 2030 World Expo host

-

Biden’s unworkable nursing rule will harm seniors

-

Jalen Hurts: We did what we needed to do when it mattered the most

-

LeBron James takes NBA all-time minutes lead in career-worst loss

-

Vikings' Kevin O'Connell to evaluate Josh Dobbs, path forward at QB

-

Lawsuit seeks $16 million against Maryland county over death of pet dog shot by police